How to Improve Self-Control by edmond EN How to Improve Self-Control

CTDP and RSIP protocols - mathematical methods to solve procrastination from first principles

zhihu-link: https://www.zhihu.com/question/19888447/answer/1930799480401293785

I hope this article becomes the most hardcore technical discussion on the topic of self-control on the Chinese internet to date (2025), bar none.

Perhaps this goal is a bit bold, but if you, the reader, have reservations, allow me to invite you to quickly scroll through and get a feel for this article’s style and content. Perhaps it will boost your confidence just a little :)

The core idea I want to convey in this article is this: The problem of self-control is not necessarily just a psychological or physiological issue. It might also be an engineering problem that can be solved with mathematics and physics. Based on this concept, it’s possible for a person to impose lasting and profound constraints on their own behavior with just a few abstract and ingenious thought experiments—without deadlines, environmental constraints, or even any external supervision—and even, to some extent, change the long-term steady state of their entire life.

(Of course, it must be specially noted that even the most powerful methodology can only partially solve behavioral problems. Many serious neurological and pathological issues still require professional medical treatment.)

To verify this idea, I, as someone who has been plagued by severe ADHD and self-control issues since childhood, have spent more than a decade from elementary school to my PhD, going through countless trials and errors, thoughts, and verifications, to gradually figure out the two generations of self-control techniques that this article will introduce.

They once helped me, without external constraints or medication, to transform from long-term struggle, unable to focus for even an hour, to being able to study at home with full concentration for several months without any external pressure, with my life in perfect order. The exploration process of these two generations of techniques is also an interesting and winding journey of trial and error and iteration on the phenomenon of “self-control.”

Therefore, I have always considered writing this article a wish that must be fulfilled: I hope to give them as a gift to those who, like my former self, are tormented by ADHD and self-control disorders. Dear strangers, I only wish it could help you, and others who are suffering, even if it’s just to solve a tiny bit of the trouble caused by self-control problems.

Next, I will slowly explain these two methods to you. They are called CTDP (Chained Time-Delay Protocol) and RSIP (Recursive Stabilization Iteration Protocol). The thinking behind these two methods is vastly different from the common, clichéd discussions that emphasize concepts like “put down your phone,” “make a plan,” “break down goals,” “reward and punishment mechanisms,” “delayed gratification,” “internal drive,” and “habit tracking.” What I want to do is to abstract the underlying mathematical and physical mechanisms from daily behavior, trying to (partially) crack the age-old human problems of procrastination, difficulty starting, giving up midway, and low-energy states from first principles, as elegantly as possible.

Of course, in this process, I will introduce some basic mathematical and physical concepts. A thorough understanding might require some foundation in first-year university calculus. But rest assured, I will do my best to use plain language for popular science, providing qualitative and semi-quantitative conceptual explanations (quantitative analysis is not realistic for this topic anyway). Additionally, to make it easier for friends with attention disorders like me to read through, this article will adopt a more colloquial writing style, interspersed with images and text, and organized using numbered paragraphs.

Finally, a small tip: During your reading, you will very likely have all sorts of questions (for example, when you read about the Sacred Seat Principle, you might think, “What if I cheat?” or “What if I become unwilling to sit on it?”). Please don’t be anxious; the next section will usually answer these questions. And many limitations of the first-generation method will be discussed and resolved in the second-generation method introduced after Section 13. In short, please read slowly, and don’t rush :)

1

Before our formal discussion, let’s consider a very common scenario:

Suppose it’s seven in the evening, you’ve just finished dinner and are sitting at your desk, in front of you is the homework you plan to finish or a paper you want to read. At the same time, your phone screen lights up, and you glimpse an interesting post on Xiaohongshu (a social media app). At this moment, you have two choices:

- Play on your phone: You get immediate relaxation and happiness. However, this seems likely to delay your study plans for the night, possibly leading to anxiety and guilt afterward.

- Go study: You face immediate boredom and fatigue. However, this will alleviate the pressure of your recent tasks and also help your academic work.

Faced with this choice, almost everyone with a lack of self-control will tend to scroll through videos for a whole night and then regret it deeply. Why is that?

This question is the most classic toy model for the problem of self-control. People have proposed all sorts of discussions about it, including countless academic concepts, rules of thumb, and folk remedies like the willpower model, dopamine, reward and punishment mechanisms, goal decomposition, delayed gratification, environmental control, psychological suggestion, identity, to-do lists, and so on.

However, in this article, I will discard all the above-mentioned clichés and vague concepts and instead use a concise mathematical model to explain it.

2

This is the first assertion of this article: When a person faces any choice, their true inclination towards a certain behavior can inevitably be expressed as the integral of the behavior’s future value function and the weighting discount function multiplied together, from the present moment ( ) to infinity:

Where:

- The Future Value Function represents the value that the behavior will bring at each future moment in your current eyes.

- The Weighting Discount Function represents how much you value the value at each future moment (the hyperbolic discount function in economics describes a similar phenomenon).

In other words, when we face a choice, we don’t just add up all “future values” and then decide. Instead, it depends on the weighted sum of values at all future moments. Generally, the weight of present value is higher, while the weight of future value is lower.

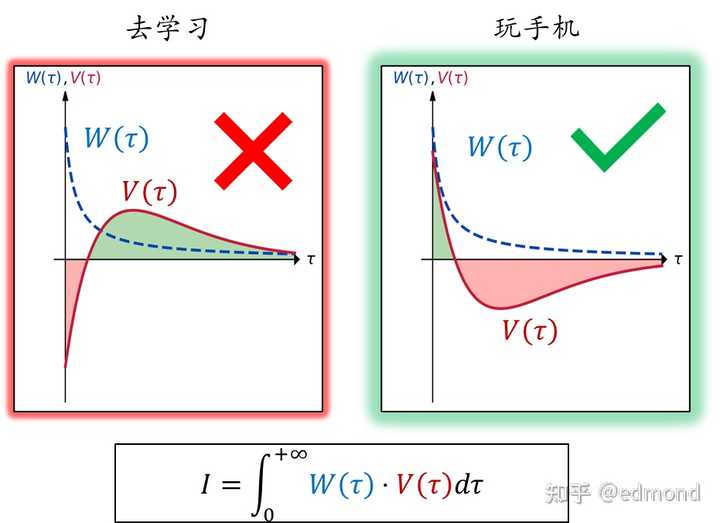

Let’s take the previous example of “study vs. scroll on phone”:

- If you choose to study, in the short term, you have to face the switching cost and the boredom of studying, so is negative. But in the medium term, the relief from pressure and the sense of satisfaction from studying turn positive. In the more distant future, the impact of one study session will eventually dissipate, and will approach 0.

- Scrolling on the phone is the opposite: In the short term, the immediate pleasure makes positive. In the medium term, however, delaying your plan causes anxiety and guilt, turning negative. And playing on your phone for one night won’t change your life, so will also slowly approach 0.

Ideally (in a purely rational case), if the weighting function were a constant, the net total value of studying would be significantly higher than playing on the phone.

However, our brains are often extremely short-sighted. The weighting function is very high in the short term and rapidly approaches zero in the long term.

Under this short-sighted weight distribution, the short-term advantage of scrolling on the phone gets a huge boost after being multiplied by the weight, and the integral result will be far higher than that of studying. This is why we ultimately choose to play on the phone.

(Note: In this article, we will treat these two functions with a “set but not solve” approach, only conducting qualitative analysis, as quantitative analysis is not realistic for this problem.)

3

In fact, you will find that this seemingly simple mathematical model can explain almost all similar classic scenarios in life:

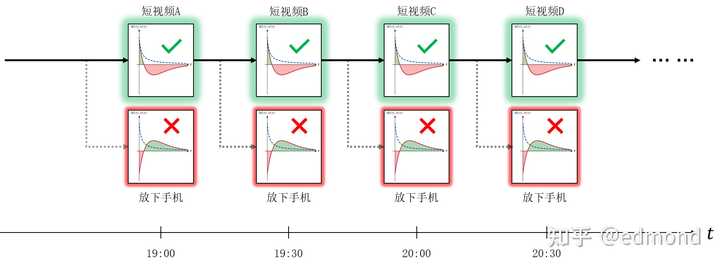

For example, let’s take the same phone-scrolling example. You finally choose to pick up your phone, thinking you’ll only play for a little while. What happens next?

From the moment you pick up your phone, the same story repeats itself indefinitely:

- After watching short video A, the short-term temptation to watch short video B will be greater than putting the phone down.

- After watching short video B, the short-term temptation to watch short video C will be greater than putting the phone down…

At every moment, it seems to you that holds true, so at every moment, you will choose to watch the next short video.

So, you end up scrolling all night, until two or three in the morning, when the cost of staying up late becomes more and more significant, gradually offsetting the temptation of short videos. Only then do you finally go to bed full of regret.

(Of course, some people, unable to face the anxiety and self-blame after staying up late, find the psychological cost of putting down the phone increasingly high, and end up staying up all night.)

But what if you had chosen to study from the beginning? You might be surprised to find that once you really get into it, continuing to study becomes easier and easier, and you even gradually lose interest in scrolling through your phone.

This is because of the “switching cost” phenomenon in psychology: when we switch from one task to another, the “switch” itself is naturally accompanied by a certain psychological resistance. This is also easy to understand in this model—to disengage from the current activity, you must first stop what you’re doing, clear the working memory loaded in your brain, and then force a switch to the new behavioral process.

This cost, mathematically, is equivalent to inserting a negative impulse function at the most sensitive position!

This is why it’s harder to climb out after falling into indulgence, but also easier to persist once a task has been started.

(For the convenience of future representation, I will not draw this switching cost impulse function separately, but will automatically merge it into the value function .)

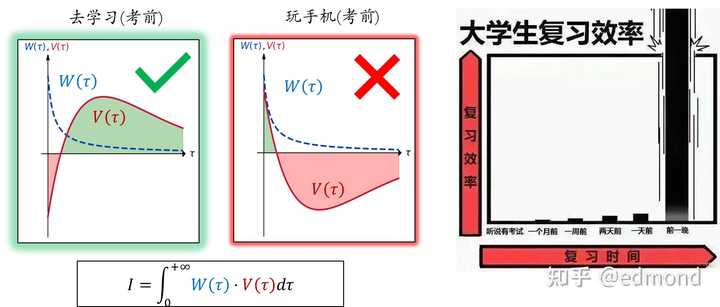

However, sometimes we can naturally resist the temptation of our phones. The review week before an exam or the eve of a deadline are such times.

As mentioned earlier, the short-term pleasure of scrolling on the phone usually only causes some anxiety in the medium term and doesn’t have a major impact on our lives.

But exam week is different—if you’re still addicted to short videos then, you’ll fail your courses, leading to a series of serious consequences that could very well change your life.

Thus, the long-term negative value of playing on the phone expands dramatically, managing to defeat the short-term temptation even with a very low weight! Therefore, the script for review week is usually a clear threshold; after a certain point in time, your time investment will suddenly increase sharply. The so-called “deadline is the number one productivity tool” is also based on this principle.

(Of course, for some people, the severity of this consequence also makes the meaning of “going to review” heavier and heavier, increasing the switching cost. The closer the deadline, the more unable they are to start, and they end up actually failing.)

There are many other examples like this. It can be said that, for a single behavior, our success or failure in self-control depends on only one thing—whether the distribution of the value function over time is favorable.

4

Since represents humanity’s innate “short-sightedness,” which is almost fixed and difficult for us to fundamentally change, we must ask a question: how is self-control even “possible”?

Here, we can make the second assertion of this article:

All effective human self-control strategies are essentially constructing a transformation of the value distribution function , so that the behavioral tendency is closer to the result of rational decision-making.

Let’s take a few examples:

- Useless Method 1 (Long-term Reward): Self-motivation, imagining the “wonderful life after future success,” or “gamification” by setting rewards for completing studies. This is equivalent to superimposing a positive linear incentive on the value function of the learning behavior in the long term. But because the long-term weight is extremely low, this method is very inefficient and usually useless.

- Useless Method 2 (Long-term Punishment): Setting punishments for playing on the phone, or going for a run or writing a self-criticism after playing on the phone. This is equivalent to inserting a negative value in the long term on the value function of playing on the phone. This method is also useless.

- Slightly Useful Method 3 (Short-term Punishment): Locking up the phone, or finding someone to supervise. This is equivalent to increasing the switching cost of indulgence in the short term, i.e., inserting a negative value into its in the short term. This method is useful, but not by much.

- Useful Method 4 (Non-linear Compression): For example, the “Pomodoro Technique” that many people are familiar with. Its mechanism is actually to transform the of “giving up midway” after starting to study, by packaging and bundling the entire sunk cost of the Pomodoro session and non-linearly compressing it to the present moment. This is a more useful method, and we will discuss it in detail later when explaining CTDP (the first-generation technique).

To measure the effectiveness of these methods more intuitively, we can also define a metric, which is the gain (G) of a self-control strategy:

Simply put, it’s the ratio of the rational decision tendency before and after using the strategy. If you use this metric to test the vast majority of mainstream so-called “self-control methods” on the market, you will find that their gains are generally pitifully low. They either only work on the far end where the weight is extremely low, or they don’t even act on the value function at all!

For example, marketing slogans like “Just do it” or “Tell yourself, you always have a choice!” can actually get thousands of likes on platforms like Zhihu and TikTok, which shows how low the average cognitive level on the topic of self-control currently is.

And those who can achieve self-control through inefficient means (many of whom are indeed excellent) do so not because these methods are so great, but because they already have good habits, environments, and personal conditions. They are only one step away from true self-control, so even a weak stimulus can push them to achieve positive behavior.

Sadly, because these advantages actually account for a very high proportion of personal achievement, people who have these advantages rarely need to pursue truly efficient self-control strategies. The superficial methods they share after their success have instead become the most widely spread mainstream cognition. We will discuss this counter-intuitive survivorship bias in more depth at the end of the article.

5

Now, things get interesting.

With this mathematical foundation, we can construct an extremely clever strategy to gain astonishing positive benefits for a single rational behavior, seemingly out of thin air, by performing non-linear compression and linear translation transformations on at different points in time.

More importantly, it can solve the three most common stubborn problems in self-control at once: difficulty starting, giving up midway, and short-lived enthusiasm.

And all of this is built on three core principles.

The first core principle is called the “Sacred Seat Principle.”

Let’s do a thought experiment:

Suppose in a certain study room, there are many seats for you to choose from freely. One day, you have a sudden idea and designate one of them as a “sacred seat,” and you set a game rule for it:

When sitting in any other seat, there are no special constraints; you can do whatever you want. But as soon as your butt touches this “sacred seat,” you must study with your best state, 100% focused, for a full hour. Conversely, if you are not confident that you can focus, then you are not allowed to sit in this seat at all, preferring to choose other ordinary seats.

In short, this “sacred seat” must not be defiled by an unfocused butt.

Of course, just imagining such a rule doesn’t have any real binding force. But what if you really executed it once?

One day, you really sat down, and the moment your butt touched that seat, you really studied in your most serious state for an hour.

Something magical happened: from the moment you successfully executed this rule for the first time, this seat, which was originally just imagined, was truly endowed with value in your mind! After that, the probability of you casually sitting in this seat and playing on your phone will be much lower than before!

Now, you add a new game rule:

Record the first successful focus session as #1. After that, each time you successfully focus for an hour, it can serve as a proof of work, adding a number to the record for this “sacred seat”: #1, #2, …, #N. But if there is a single failure—for example, you scrolled on your phone on it, or you only sat for ten minutes and left—then all records will be cleared, and you have to start over from #1 next time.

As this chain continues to lengthen and the proof of work continues to accumulate, the value of this fictional seat will be enhanced time and time again. When this “focus task chain” grows to #10, #20, #30, the constraint of this rule almost becomes substantial—you might even become cautious and careful, afraid to even breathe too loudly, for fear of any slight disrespect to the rule.

(I’m sure the clever you has thought about the problem of this rule collapsing + you not being willing to sit on it. Don’t worry, this is exactly what sections 8 and 9 will solve.)

(To avoid misunderstanding, I need to state that this is not the final version of the method. What really works is the mathematical mechanism, which has nothing to do with so-called “morality,” “ritual,” “psychological suggestion,” or “now or never.” This will be explained in detail later.)

6

This magical binding force actually comes from the innate human obsession with “maintaining a record.”

Many fitness or learning apps have a “consecutive check-in” feature. Many people, no matter how tired or sleepy, will force themselves to memorize words for 5 minutes just to maintain that “365-day consecutive check-in” record on Duolingo. People who have quit smoking or drinking for 10 consecutive days will find it harder to give up when they see the number 10 than on the first day.

—Just an imagined record is enough to produce an almost absurd binding force.

Upon closer examination, this binding force actually comes from two points:

- On the one hand, the longer the record is maintained, the more real time and energy you have invested to maintain it. Behind every successful task node on the chain is real “proof of work” and sunk costs.

- On the other hand, this record is often accompanied by a wonderful “future value expectation”: you think this record is valuable → you are afraid of losing this record → it will produce a binding force → this binding force will help your future self-control, and your future self-control depends on it → this record becomes more valuable. The higher the value, the stronger the binding force; the stronger the binding force, the higher the future expectation; the higher the future expectation, the higher the value…

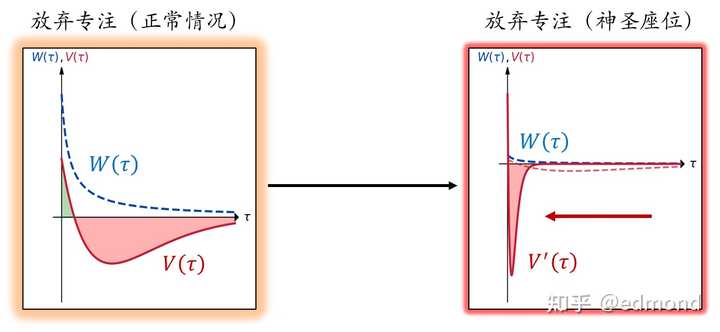

However, all “records” naturally have the characteristic of “all for one, and one for all”: once you break this record, all the hard-earned sunk costs and future expectations will be immediately and suddenly lost at the instant of !

This is the underlying mathematical essence of the “Sacred Seat Principle”: a non-linear compression transformation of .

When you are sitting in this seat, the value invested in all past nodes of the entire task chain, and the future expected value, will be sharply compressed in the value function of the “give up focus” option, condensed into a negative spike extremely close to the origin ()—any short-term temptation to break the rule must immediately face the challenge of the entire chain’s accumulated and future value.

And the most wonderful thing is that this holds true at every moment of the focus task. When the sunk cost accumulates to a certain level, no short-term temptation will be able to challenge such an amazing barrier.

7

This “all for one, one for all” value bundling principle is also the reason why many classic self-control strategies really work:

For example, the Pomodoro Technique. Each Pomodoro session is actually like a “small-scale sacred seat”: it packages and bundles the sunk costs and future expectations of the entire focus period into a single “Pomodoro.” Once you slack off or give up during the Pomodoro session, you immediately have to bear the huge cost of losing the entire “Pomodoro” in the present moment.

In this way, the trade-off you make at every moment is no longer a comparison between “immediate temptation and the current task,” but a competition between “immediate temptation and the total value of the compressed Pomodoro”—this is the truly effective core mechanism behind the Pomodoro Technique.

For another example, many people have had this experience:

One day you learn a new self-control method, you find it very reasonable, and you eagerly put it into practice. At the beginning, even if the method is actually useless, you will find it miraculously effective.

But strangely, after a few days, the initial novelty wears off, you start to violate the rules frequently, the effectiveness of the method rapidly decays, and it eventually fails completely and is abandoned by you.

This is an illusion similar to a “newbie protection period”: any self-control method seems useful in the first few days, but what really works may not be the method itself, but your “future expectation” of this method.

When you pin your hopes for future self-control on this method, this “pinning of hope” temporarily, and truly, endows it with binding force. However, if the method itself is inefficient, this temporary binding force will eventually be unable to support its long-term survival in a complex real environment. Once any violation or wear and tear occurs, the credibility and value of the entire method will rapidly collapse with the broken window effect.

And the most beautiful thing about the “Sacred Seat” design is that it is naturally a distributed, decentralized design in time. It is only responsible for the selected, purified state of sitting in that seat, and does not need to be exposed to all times and be responsible for the long-term state, thus maximizing the avoidance of wear and tear.

In other words, you can go to a party, drink, play games, and waste days or even a week after completing task #1 in a full state. But when you walk back into the study room to start #2 next time, the sacred seat is still that sacred seat, and its binding force will not be weakened in the slightest.

8

Of course, even in this selected state, the “Sacred Seat Principle” is not completely without loopholes.

As mentioned earlier, once you sit in this position, you must focus and study for an hour in the “best state.” The question then becomes, how do you define this “best state”?

- If I go to the bathroom in the middle, does it still count as the “best state”?

- If I answer a phone call or pick up a package, does it still count as the “best state”?

- If someone messages me and I reply, does it still count as the “best state”?

- If all these count, then playing on my phone for a bit, scrolling through a few short videos, can also be considered the “best state,” right?

You will find that the “ideal state” simply does not exist. Any self-control strategy, once put into practice, must face complex and ever-changing real situations. On the surface, a self-control strategy is just a simple constraint; but in actual application, all self-control strategies are equivalent to a large number of implicit, tiny “sub-constraints,” each of which can be tested and challenged:

- If you allow yourself the flexibility of free discretion, the binding force of the method will be continuously eroded in one “this time is special, it won’t be a precedent”侥幸心理 (lucky mentality) after another, creating a broken window effect, and eventually being corroded beyond recognition.

- But if you do not allow any exceptions at all, the method will become rigid and fragile. When you encounter a situation that is truly unbearable, the rule may collapse instantly and completely.

This “gradual broken window effect” is the fundamental reason why most methods similar to “gamification” or “setting rules” will fail sooner or later. It’s not important what game the athlete plays; what’s important is the logic of separating the athlete and the referee.

To solve this problem, let’s introduce a more ingenious second core principle: the “Next Time It’s a Must” Principle.

(Note: This is a play on the Chinese idiom “下不为例” (xià bù wéi lì), meaning “it won’t be a precedent.” The author changes “不” (bù - not) to “必” (bì - must).)

Since you yourself know very well that once you have the first “it won’t be a precedent,” there will inevitably be countless subsequent acts of cheating. So, why not do the opposite and force yourself to “make it a precedent next time”—that is, in reverse, require yourself to cheat in the future!

Specifically, when you face any judgment of a suspected violation, just like the “case law” in the Western legal system, you can only choose one of the following two options:

- Immediately judge that the rule of the “sacred seat” has been completely broken, the chain is broken, all task records are completely cleared, and admit that the binding force is completely zero. You have to start over from #1 next time.

- Judge that this behavior is allowed, but, once it is allowed this time, it must be allowed in all similar situations in the future. For the entire life cycle of this task chain, it will completely lose its binding force on that behavior.

Your “best state” is not defined by any subjective or objective standard, but is dynamically defined by countless “precedents”:

- Going to the bathroom midway, does it still count as the “best state”? It can, but as long as it counts this time, it must count in the future.

- Replying to a message midway, does it still count as the “best state”? It can, but as long as it counts this time, it must count in the future.

- Scrolling through short videos for two minutes midway, does it still count as the “best state”? It can, but as long as it counts this time, it must count in the future.

In this way, what you are considering is no longer an isolated choice, but whether to permanently give up the rule’s binding force on that behavior at this very moment. The cost before you is the true long-term cost of allowing this behavior.

Now in your eyes:

- For behaviors that rationally should not be allowed (e.g., playing on the phone), when you are sitting in the seat, you are very clear: as long as you allow this “exception” today, then every time you sit in this seat in the future, you will cite this behavior as a “precedent” to cheat (and the rule requires you to cheat), and you can never redefine this behavior as a violation.

- And for situations that rationally should be allowed (e.g., going to the bathroom), you in the future can also let yourself off the hook with a clear conscience, without any concern for the credibility of the rule.

In the end, the judgment you make really becomes the decision that is most in line with long-term rationality. Because, you who are thinking for the present (as the athlete), and you who are thinking for the future (as the referee), have miraculously reached a consensus under this mechanism—just like that, you and yourself have reached a Nash equilibrium across time.

When this method is run for a long time, the boundary of the rule’s constraint will not gradually corrode and collapse like traditional methods, but will slowly, in an fashion, with a precision that is “always just enough,” gradually converge to the boundary that is closest to rational decision-making: it can both tolerate truly necessary exceptions and effectively prevent unnecessary self-indulgence.

This is the ingenuity of the “Next Time It’s a Must” principle.

9

Alright, now we have a perfect “sacred seat.” But a new problem arises:

The more sacred the seat, the more you will be afraid to sit on it.

Indeed, the state of sitting in this “sacred seat” is perfect. However, this seat is so sacred, so perfect, that the commitment of the action of “sitting in the seat” is too heavy. You will become more and more unwilling to sit on it, which is the commonly known problem of “difficulty starting.”

This is precisely why people always say “perfectionism leads to procrastination” (strictly speaking, the essence of procrastination is not perfectionism, but the increased switching cost caused by excessively high expectations).

At this point, it’s time for our third core principle: the “Linear Time-Delay Principle.”

And this principle, from a mathematical perspective, can elegantly crack the “procrastination” problem that has troubled countless people for a long time in one fell swoop.

Let’s do another simple thought experiment:

- Suppose you find a typical procrastinator and ask him: “Are you willing to start studying right now?” He would most likely shake his head and refuse.

- But if you ask him in a different way: “Then are you willing to start studying tomorrow afternoon?” Or even not that far off: “How about starting in 15 minutes?” This time, he will most likely agree! And, the longer this delay, the higher the probability that the person will agree.

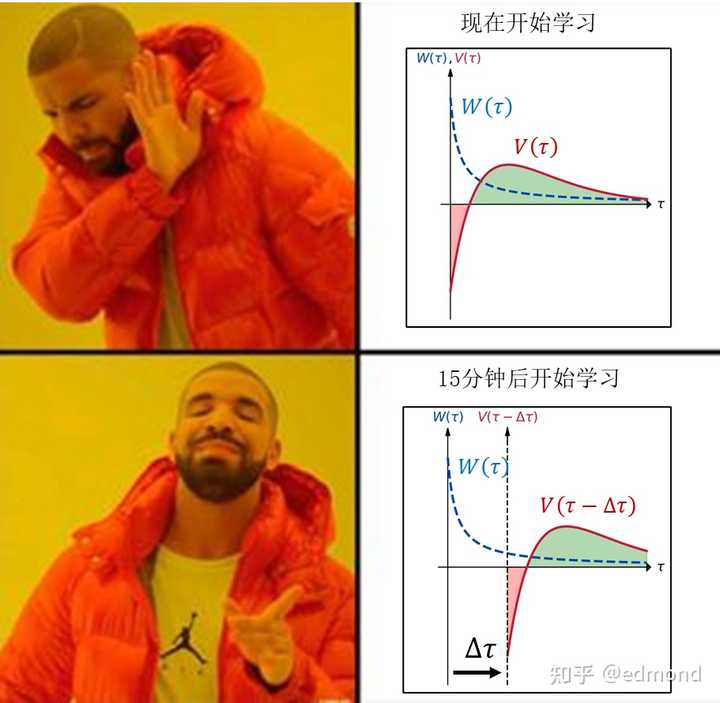

Why does this strange phenomenon occur?

Let’s go back to the mathematical model we discussed earlier to explain:

- When you consider “whether to start studying right now,” as analyzed before, the negative value of the value function is located in the high-weight recent period of the weighting function , so you feel strong resistance.

- However, when you consider “whether you are willing to start studying in 15 minutes,” the situation is completely different: this is actually equivalent to shifting backward on the time axis by 15 minutes, to a relatively flat region of ! Compared to the option of indulgence, this almost erases its huge disadvantage in the short term.

This also explains a very common phenomenon in daily life: we always have blindly optimistic fantasies about our future self-control.

In the hyperbolic discounting function, the decrease in weight over time is steep at first, then slow. The weight after 10 minutes and the weight after 1 hour may be worlds apart, but the weight after 1 day and 10 minutes, and the weight after 1 day and 1 hour are almost the same.

When we consider future choices in advance, it is equivalent to shifting and then integrating with . The longer the shift distance, the flatter the actual involved in the integration, and naturally the closer to the rational state. This is why we are often blindly optimistic when making summer vacation plans, and why we naively think we can really put down our phones after scrolling for five minutes.

And here comes the climax of this method:

We can establish a parallel “auxiliary chain” in addition to the main task chain, also protected by the Sacred Seat Principle, and also applying the “Next Time It’s a Must” principle to all situations. Its defended rule is very simple:

- Set a simple action as a reservation signal, such as snapping your fingers.

- Once this signal is triggered, you must, within the next 15 minutes—SIT! DOWN! IN! THAT! SACRED! SEAT!

As the saying goes, it’s better to channel than to block. The best way to overcome procrastination is to first acknowledge and respect procrastination.

Since the threshold for “reserving to start in 15 minutes” is much lower than the threshold for “starting immediately,” you can now initiate the reservation without any pressure.

After 15 minutes, the past and future value of that auxiliary chain will gradually compress and condense at into a sharp, sky-piercing firing pin—forcefully breaking through the gate of “switching cost” and “difficulty starting.”

(A side note and an embarrassing story: when I first came up with this method, one night I couldn’t sleep and accidentally snapped my fingers. I had no choice but to get up at 3 am and study for an hour.)

Now, combining the three core principles from before, we finally have the complete first-generation self-control technique:

Chained Time-Delay Protocol (CTDP)

10

Here is the complete description of the Chained Time-Delay Protocol (CTDP):

CTDP is a behavioral constraint strategy constructed based on three core principles (Sacred Seat Principle, Next Time It’s a Must Principle, Linear Time-Delay Principle). Specifically, it requires you to build two parallel task chains (a main chain and an auxiliary chain) and strictly follow these steps:

Main Chain (Task Chain):

-

First, designate a specific object as a marker, serving as the “sacred seat” (in fact, the sacred seat is just a metaphor; it can be anything—a specific chair, a special pen, a hat, or even a message sent to a specific alternate WeChat account of yours).

-

Once you trigger this marker, you must complete a well-defined focus task in your “best state.”

-

Every time you successfully complete a focus task, you can record a node in the main chain: the first success is #1, the second is #2, the third is #3, and so on.

-

If, during any task, you seem to have acted in a way inconsistent with the “best state,” you must choose one of the following two options (“Next Time It’s a Must” principle):

a. Declare the entire main task chain an immediate failure, clearing all currently accumulated node records. The next attempt must start over from #1. b. Permit the current behavior, but from now on, this behavior must be permanently permitted in all subsequent tasks and can no longer be considered a violation.

Auxiliary Chain (Reservation Chain):

-

Define a simple reservation signal, such as snapping your fingers or setting an alarm, to indicate that the main task will begin in 15 minutes.

-

Once you trigger this reservation signal, you must trigger the marker corresponding to the sacred seat within the next 15 minutes to start a main chain task.

-

If, after triggering the reservation, you do not trigger the marker within 15 minutes, the “Next Time It’s a Must” principle also applies:

a. Either completely clear the records of the reservation chain, acknowledging its failure. b. Or permit the current situation, but from then on, the reservation chain will completely lose all its binding force over that situation.

Thus, by simultaneously using the triple mechanism of non-linear value compression (Sacred Seat), case-law-like constraint (Next Time It’s a Must), and linear time shifting (Reservation Mechanism), we have hacked the effects of difficulty starting, the broken window effect, and short-sighted decision-making.

With just a few thought experiments, we have constructed a self-control strategy that, without external supervision or even sufficient willpower, can gain enormous leverage for rational behavior seemingly out of thin air. Moreover, its binding force comes entirely from the proof of work of each node, and it is only responsible for these distributed, selected nodes, so it is not exposed to long-term state fluctuations and thus not subject to corrosion.

Relying on this CTDP strategy, for any important task, we can make it both easy to start and easy to persist in, and it won’t fail in the long run—this seemingly impossible triangle, we get to have it all.

11

Of course, the CTDP described earlier is more of an idealized version. In real life, its application is far more flexible and interesting than what was just discussed.

For example, does the “sacred seat” really have to be a seat?

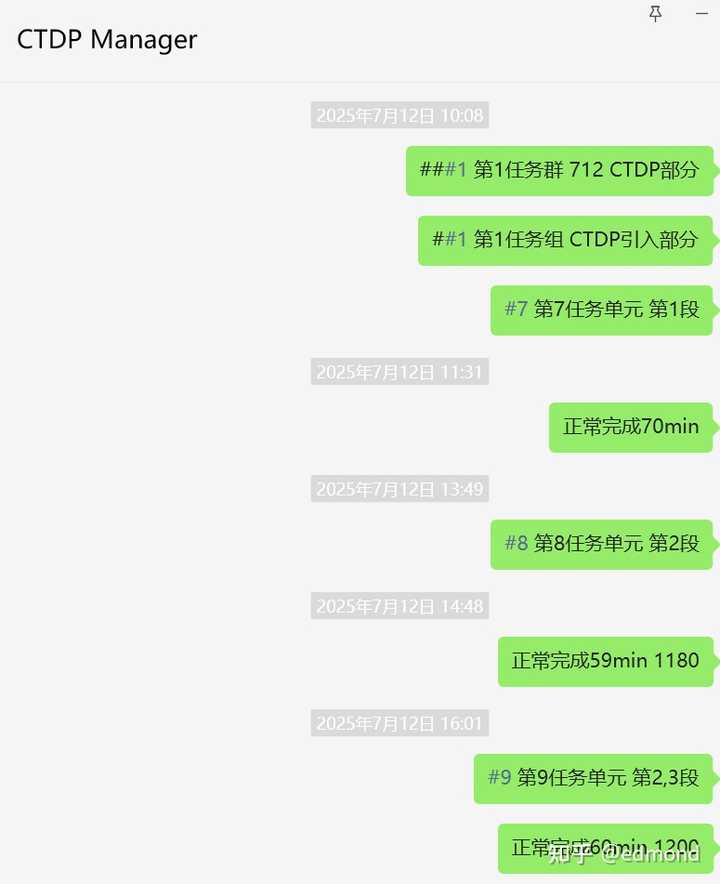

Not necessarily. It can be any specific, easily distinguishable marker. For instance, the marker I usually use is a dedicated alternate WeChat account. Every time I start a task, I send a message to trigger the task, and at the same time, record the node and a declaration of intent.

Secondly, the task chain itself doesn’t have to be a strict linear progression (#1, #2, #3…). You can totally construct a top-down hierarchical organization:

- For example, three unit-level nodes can form a 3-hour task group, denoted as ##1.

- Three task groups can form a day-level task cluster, denoted as ###1.

- Three task clusters can form a three-day-level task column, denoted as ####1.

- Two to three columns can be managed by a week-level task echelon, denoted as #####1.

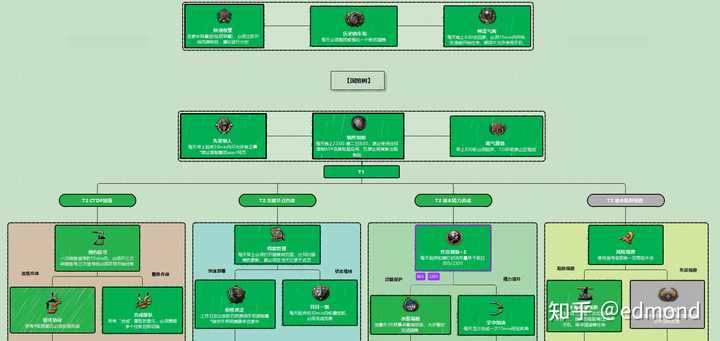

And each unit can have its own requirements. For example, a ## task group can require that a reservation signal be executed after the first two # units are completed, thus stringing the three # units together. In this way, like a military command sequence, we organize the massive task chain from top to down in a “three-by-three” manner!

Similarly, the content of the task units doesn’t have to be monotonous focused study. To put it in a more “chuunibyou” way, they can be divided into different “military branches.”

For example, studying, doing experiments, reading papers = “Assault Unit,” information gathering = “Reconnaissance Unit,” making plans = “Command Unit,” handling chores = “Special Operations Unit,” exercising = “Engineering Unit,” preparing meals = “Quartermaster Unit”…

And a large task cluster or task column can be composed of multiple branches, like a modern combined arms unit—

A main combat task cluster focused on work could be composed of 7 assault units + 2 reconnaissance units.

A weekend rest and logistics task cluster could be a combination of 1 command unit + 3 special ops units + 2 engineering units + 1 quartermaster unit.

During a holiday, a three-day-level column that balances exercise and self-study could be formed by combining 6 assault groups + 3 engineering groups.

You will find that this task chain structure naturally accomplishes what people often call “goal decomposition.” At the same time, “gamification” doesn’t need to be deliberately designed—because when you are truly faced with a large task, the scene is like this:

Schedule, take this down, I am making the following deployment adjustments:

Reinforce the deadline defense line for next week’s homework with the 4th Task Group, 11th Task Group, plus the 15th and 16th independent recon squads. The 2nd, 3rd, 7th, 8th, and 9th Task Groups, plus the 17th Assault Squad from the 6th Task Group, will concentrate their forces to complete the notes. The 10th Assault Group plus one assault squad will hold the line on the TOEFL and GRE front, intercepting vocabulary that encroaches on review time. The 12th Task Group, in coordination with twelve independent units, will encircle and destroy the knowledge gaps previously identified. The 5th Task Group and the two recon squads from the 6th Task Group will gather intelligence. The 14th Task Group will act as the general reserve, do not move!

Some asides:

In practice, using just one simple reservation signal is still too fragile, because sometimes when the 15 minutes are up, I might be in the bathroom/outdoors, and starting the task isn’t realistic. So, I would design two activation signals as a buffer:

- Reservation Activation Signal: The signal is snapping my fingers once. Once triggered, the “Immediate Activation Signal” must be executed within 14 minutes and 30 seconds (reserving a buffer, to prevent using up the full 15 minutes).

- Immediate Activation Signal: The signal is snapping my fingers three times. Once triggered, I must start the task [as soon as possible] according to the current conditions.

Furthermore, this strategy, a combination of “sacred seat + next time it’s a must + linear time-delay,” can be easily extended to any aspect of life:

- For example, to start running, you can use a specific hand gesture as a reservation signal. Making the gesture n times means you must run for 5×n minutes.

- To solve the common procrastination problems with showering and going out for people with ADHD, you can also set up corresponding reservation signals for showering and going out.

Extended even further, you can almost “remote control” your daily life with simple gestures or actions—in an extremely easy and elegant way, completely eradicating the problem of procrastination.

12

At this point, the content of the first-generation self-control technology has been fully presented.

Looking back, this set of techniques, whether in terms of principle design, practical implementation, or the ingenuity of the methods, has far surpassed the superficial motivational slogans, to-do lists, or gamification designs on the market.

Sure enough, in the years after CTDP was born, it produced astonishing effects on myself.

I must confess that my own foundation in self-control is truly terrible: I was addicted to games day and night from elementary school to high school, suffered from ADHD for years, and my study habits and life order were a complete mess. I couldn’t pay attention in a single class from childhood, and I was lucky to get into a 985 university (a top-tier university in China). In the early days of university, when the environment became more relaxed, I could even slack off and not study properly during exam week. The example I gave earlier of studying less as the deadline approached was a true reflection of my past self. My self-control foundation was at rock bottom.

But since the birth of CTDP, for the first time in my life, I achieved sustained self-discipline for weeks or even months. With this technique, I could start tasks with extreme ease and maintain a full day of high concentration without any burden. The problem of ADHD seemed to be alleviated overnight. Not only did my university grades improve significantly, but I also managed to go on an exchange abroad, publish papers, successfully conquer the TOEFL and GRE, and eventually complete a hardcore master’s program.

Especially during my peak periods (such as preparing for the TOEFL and GRE), it could mobilize me to work efficiently for 8-10 hours a day for two consecutive months. Dozens of task clusters and hundreds of task units could be commanded with precision, advancing and retreating in an orderly and seamless manner.

There was even a time when I caught a cold for three days during an exam review period, and I was still able to calmly calculate its impact on the exam fifteen days later and composedly redeploy eight or nine ##-level task groups from the general reserve deployed seven days later to fill the gap.

(For example, this is a plan for more than a month before an exam, where each cell represents a ##-level task group)

In the face of such unprecedentedly efficient self-discipline, I was once optimistic that the edifice of self-control had been built, and all that was left was some patching up.

However, I soon discovered that CTDP was not always effective. Specifically, I observed a clear polarization phenomenon:

- When the overall state was already favorable for self-control, especially when there were clear pressures and goals like deadlines, such as during the review period before an exam or when there were many urgent tasks, CTDP could indeed maximize the use of these pressures, allowing self-discipline and orderliness to reach unprecedented heights. I could command almost every hour with ease and proficiency.

- However, when the overall state was not favorable for self-control, such as during idle time at home, when I was physically and mentally exhausted, or when there were no clear task goals, I often lacked even the will to trigger the reservation activation signal. Even if I forced myself to start multiple times, it would collapse after just a few # tasks.

Therefore, over the next three to four years, I tried countless times to improve and upgrade it. However, CTDP seemed to have exhausted the limits of self-control strategies from the micro-perspective of a “1-hour scale single behavior.” No matter how it was modified, it failed to make any progress over several years, and my self-control state always showed strong periodicity and environmental dependence.

Thus, this bottleneck troubled me for several years. It wasn’t until five years later that I finally found a more profound perspective to explain it all.

—Not by focusing on the traditional “motivation,” “reward and punishment,” or “constraint,” but by looking at the entire system from the perspective of “scale”!

13

Under this new perspective, the various behaviors in our lives are not composed of simple, isolated decision nodes described solely by the immediate . In reality, it’s more like a “behavior tree” composed of countless continuous, intertwined decision nodes.

In this behavior tree, the direction of each node is highly dependent on the choices of the nodes before it; and its macroscopic direction at various time scales is, in turn, highly determined by various large and small scale factors in life. And the vast majority of these nodes are precisely unsuitable for our limited free will, or for self-control strategies driven by free will, to intervene in.

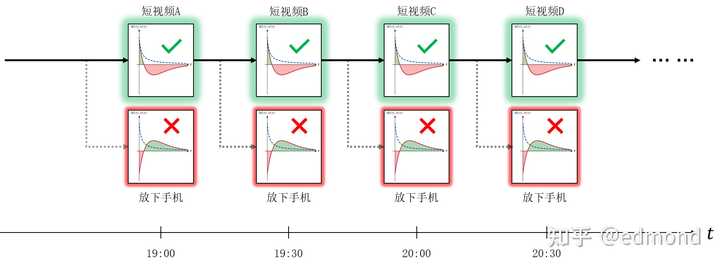

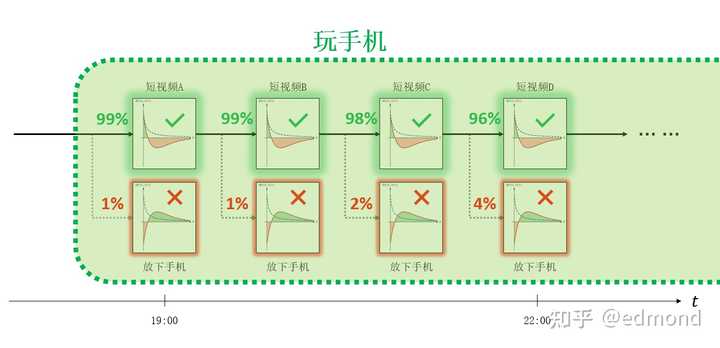

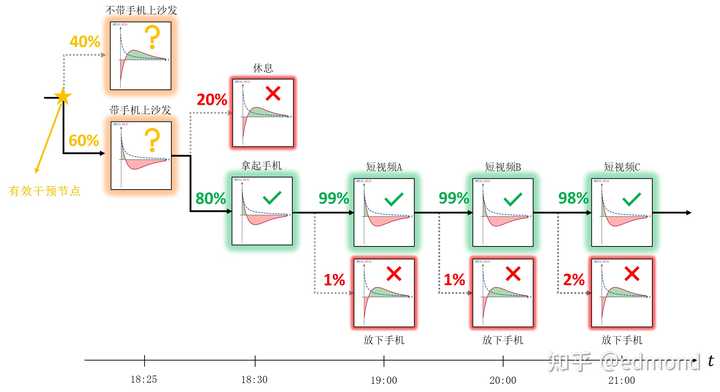

Let’s recall the phone trap example from the beginning:

One evening after dinner, you lie on the sofa with the mentality of “just scrolling for a little while” and casually open a short video app:

As analyzed earlier, after each video, you once again face the micro-choice between “scrolling the next video” and “putting down the phone.” But unfortunately, the relationship holds true for every micro-node, so you can’t put down your phone at any node.

If we were to calculate the probability of you eventually choosing one of the two branches based on all your past choices, you would find that the disparity between them is extremely large—perhaps as high as 99% to 1% (this is just a conceptual example, no actual statistics needed).

Now, we can introduce a key assumption—the “Limited Free Will” hypothesis:

Free will exists, but it is limited. The smaller the preference gap between options, the higher the probability that free will can effectively intervene. If it’s a 60%:40% gap, free will can still intervene; but when the gap between options is too large, say 99%:1%, free will is almost powerless.

In fact, the moment you lie down on the sofa and open the short video app, your behavioral state is like a fighter jet locked on by a missile’s radar, trapped in an “inescapable zone.” Within this zone, you cannot break free from the inside with just the minor struggles of free will. Statistically speaking, you can only wait for your doom.

It’s not until the anxiety of staying up late slowly grows, and the numbness from scrolling through your phone slowly builds up, that the preference gap between the two options gradually narrows to a range where free will can intervene, and you can successfully exit this state.

In other words, the moment you chose to pick up your phone and lie down on the sofa, you had actually already decided, in a larger-scale sense, the next few hours of wasted time.

Based on the above observations, we can propose a further definition:

When the probability gap of a series of decision nodes exceeds a certain threshold (e.g., 90%:10%), we can consider it beyond the intervention range of free will. Then, we can directly ignore the option with the lower probability and approximate these micro-nodes by coarse-graining them into a single “inescapable zone.”

If we look at it from a larger scale, inside these “inescapable zones,” those seemingly independent decision nodes have already been determined in a statistical sense by larger-scale factors (such as immediate temptation, current mood, physical fatigue, and deep-rooted habits). The small-scale choices of free will, such as whether to watch videos or play games, and which specific short video to watch, become unimportant.

14

This phenomenon, where the importance of various influencing factors waxes and wanes at different scales, is not limited to the field of self-control but exists widely in all kinds of complex systems.

In statistical physics, there is an elegant and profound theory called “Renormalization Group Theory,” which describes this very phenomenon. In 1966, the American physicist Leo Kadanoff proposed this idea:

When you change the scale of observation, the internal degrees of freedom of the system are continuously merged (coarse-grained), the macroscopic behavior of the system gradually becomes dominated by a few key variables, while a large number of microscopic variables gradually become unimportant.

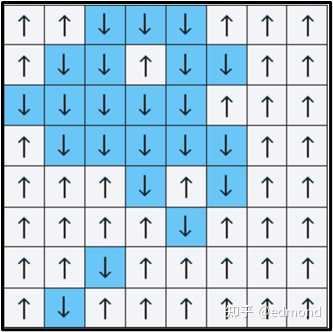

To simply understand this method, let’s imagine a small game:

You have a large checkerboard in front of you, and each square has an arrow, either pointing up (↑) or down (↓). We can design some rules to influence the direction of the arrows, for example:

- We can add a rule that makes each arrow tend to align with its neighbors.

- Or conversely, make the arrow tend to be opposite to its neighbors.

- We can also add local noise and disturbances.

- And sometimes, we can even apply overall external intervention.

Under these densely interwoven local rules, many small disturbances, even a tiny change in one square, could spread to the surroundings, forming complex chain reactions. You might think that to analyze the overall pattern, you would have to account for every single arrow.

But Kadanoff said: It doesn’t have to be that complicated. As long as we are willing to be a bit “blurry,” to look a bit more “coarsely,” the patterns will automatically emerge.

He designed a clever “coarse-graining” game rule:

- Merge adjacent 2×2 small squares into one large square.

- Use a “winner-takes-all” method to decide the direction of this large square (e.g., if there are three ↑ and one ↓, the whole block is recorded as ↑; if the numbers are equal, randomly choose a direction, or handle it according to some simple rule).

- Then, continue to repeat this merging operation with the newly obtained large squares…

After rounds of “merging” and coarse-graining, our perspective gets further and further away, more and more blurry. The arrow map that looked chaotic in detail at the beginning eventually boils down to just a few large regions, perhaps with most directions tending to be the same.

What happened in this process?

- First, those local rules with a small scope of action, acting independently, will be submerged or averaged out during the merging, eventually disappearing completely on a large scale. The structures they created will therefore gradually diminish.

- Conversely, those trends that are broader and more consistent are able to survive each layer of coarse-graining and gradually stand out on a larger scale.

- Thus, this coarse-graining not only changes the squares but can also change the strength of the “rules” themselves! Whether a rule is important depends on the scale at which you look at it. Factors that are crucial on a microscopic scale may leave no trace on a large scale; while those seemingly weak but consistent trends may become the ultimate driving force of the system.

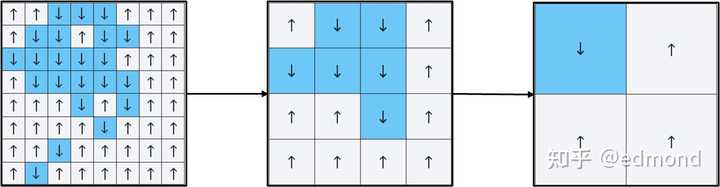

Let’s consider a simple example.

Suppose on this checkerboard, two forces are competing with each other:

- One is a short-range exchange interaction, very strong, but only affecting the nearest neighboring squares, causing adjacent arrows to tend to align.

- The other is a long-range dipole interaction, relatively weak, but able to act over longer distances, trying to make the arrows in a region point in opposite directions.

(Note: In the real world, there may also be complex factors like anisotropy, thermal fluctuations, defects, stress, etc. This is just a very simplified heuristic discussion.)

In the absence of external intervention, a tug-of-war begins between these two forces:

- The exchange interaction tends to pull all the local squares in the same direction, forming a large number of small, locally aligned regions.

- The dipole interaction does not allow the entire system to stay in the same direction for too long; it tries to “pull” these regions from a distance, prompting them to alternate directions and form arrangements that cancel each other out.

Ultimately, under the competition and compromise of these two forces, an exquisite balance is reached: you will see large patches of arrows automatically gather, forming “islands” of various sizes and alternating directions. Within each island, the direction is uniform, while different islands have different directions. These islands are intertwined, eventually stabilizing into a complex yet stable “jigsaw puzzle” structure.

In the real world, this phenomenon is known as “Magnetic domains,” and it is the result of the classic competition model between short-range exchange and long-range dipole interactions.

15

So, what happens when we observe this checkerboard at different scales?

- At the microscopic scale, we mainly see patches of highly uniform local regions: At this point, the exchange interaction is very powerful, quickly causing the surrounding squares to align in the same direction; whereas the dipole interaction, being too weak, is almost imperceptible from this microscopic perspective.

- But when we coarse-grain to a larger scale, what we see are large blocks with alternating directions: At this point, although the exchange interaction is strong, its range is too short, only affecting the uniform trend within small scales. Its influence does not grow with coarse-graining. Conversely, the dipole interaction has a long enough range. At a large scale, its weak effects continuously add up and slowly accumulate, gradually becoming dominant and forming a distinct macroscopic structure.

This phenomenon is the most profound point revealed by the idea of the renormalization group.

The importance of a factor often depends on the scale of observation you are at—a rule that is crucial at a small scale may be completely averaged out at a larger scale; while those long-range trends that are almost imperceptible at a small scale may accumulate layer by layer during the coarse-graining process and ultimately dominate the macroscopic direction of the system.

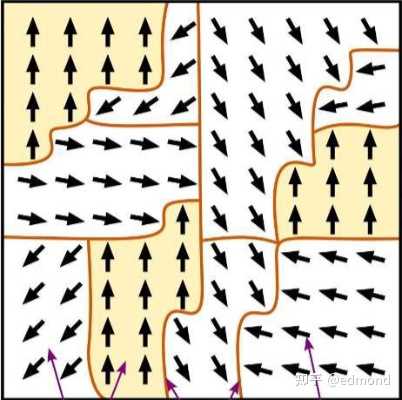

![Application of renormalization group ideas to different research objects. Source: Klemm K. A zoom lens for networks[J]. Nature Physics, 2023, 19(3): 318-319.](https://picx.zhimg.com/50/v2-3217cfd3d8d0d60974b968af184b9c4b_720w.jpg?source=2c26e567)

This is one of the most universal laws in the entire physical world:

- A glass of water at the microscopic level is the complex and disordered collision of countless molecules, but at the macroscopic level, it can be completely described by just a few simple variables: temperature, pressure, and volume.

- The magnetic moments of a magnet are chaotic at the atomic scale, but at the macroscopic scale, they condense into clear north and south poles.

- Each atom in a spring obeys complex quantum mechanics, but from the outside, macroscopically, it’s just a simple Hooke’s law .

- In financial markets, no matter how complex the short-term trends are, they will ultimately follow the script set by the long-term trends.

As the observation scale continues to expand, most local fluctuations, short-range variations, and microscopic rules are automatically merged, canceled out, and absorbed into other variables. The final macroscopic behavior of the system depends only on a very small number of variables that have a wide range, strong consistency, and can continuously accumulate and survive at larger scales.

(Note: These two sections are only meant as enlightening analogies for life, not as rigorous reasoning.)

16

The frightening thing is, ideas like renormalization can actually be extended to life itself.

Let’s look back at the rule we set earlier: when the statistical probability gap between options exceeds a certain threshold (say, 90%), we consider it beyond the intervention of free will and treat it as an “inescapable zone”—you’ll find that most of our time is made up of “inescapable zones” of various sizes, pieced together like magnetic domains.

When you’re lying in bed late at night scrolling through short videos, that’s a negative “inescapable zone.” You’re highly unlikely to suddenly put down your phone midway.

When you’re eating, that’s another inescapable zone. You’re highly unlikely to suddenly stop eating and go to the library to study.

When you’re studying, that’s a positive inescapable zone. Once you get into the flow, you won’t easily stop unless you hit a roadblock.

You might say, “Wait, don’t we always have moments where we still have a choice?”

But unfortunately, if you pull back to a larger scale, those superficial freedoms are enveloped by even larger “inescapable zones”:

- You only slept for three hours last night. Your script for the day is likely to be a total write-off. Even if you choose to start studying, you’ll find it hard to persist. You’ll converge to an “inescapable zone” of being tired while scrolling on your phone, relying on the high stimulation from your phone to stay awake.

- If you have absolutely no deadlines for the next few days and are just lazing around at home, you’re likely to fall into a continuous cycle of “alternating between phone and games.” This is also a macro-scale “inescapable zone.”

- As the final exam deadlines loom, your script for the month is often to be lazy and procrastinate at the beginning, then easily get into a study state a few days before the exams, and finally regret not starting earlier.

My friend, the truth of our lives is a series of nested scripts, cycles, and inescapable zones, like Russian dolls.

How many ways can we spend a minute? Perhaps hundreds or thousands: you could be scrolling through short video A, or short video B, reading a book, or working on a specific problem.

But if we zoom out the time scale a little, there might only be a few dozen ways to spend an hour: maybe just scrolling videos/studying/commuting/eating.

Zoom out to a day, and there might only be a dozen or so ways. To a month, perhaps only seven or eight typical patterns. And if you zoom out to the scale of a year, you might be surprised to find that our year consists of only three or four general scripts.

As our perspective widens and we coarse-grain the entire chain of events, the influence of small-scale details diminishes, getting averaged out. The entire system becomes increasingly dominated by the corresponding large-scale factors, like environment, work, habits, personality, and so on. Small-scale variables control small-scale scripts, and large-scale variables control large-scale scripts:

- Your state of attention controls your thoughts every second.

- The task at hand directs your attention every minute.

- Today’s schedule determines what you do each hour.

- Your energy and emotional state over the last few days influence your daily arrangements.

- Further up, your sleep patterns, emotional cycles, and environmental conditions control your overall state of life in the near term.

- And your identity, personality, and social circumstances determine your long-term rhythm, ultimately shaping the entire appearance of your life.

At each specific scale, once the corresponding factors are given, they become a stable “boundary condition,” causing the system to spontaneously form several clear and stable “steady states” within that scale.

Downward, each steady state is composed of a combination of several smaller-scale steady states. Upward, several such steady states further combine to form a larger steady-state structure.

These steady states are highly stable, highly repetitive, and highly dependent on those key factors at the corresponding scales. It is these influencing factors and steady states of various sizes, intertwined, that together form the “ecological environment” of our daily lives.

Viewed this way, “free will,” located at the very bottom layer, is truly the greatest illusion in life.

We completely possess free will every second, seemingly possess free will every minute, somewhat possess free will every hour, but by the time we get to every day and every week, we don’t seem to possess much free will anymore. On a macroscopic level, we are just like duckweed in a vast ocean of environment, habits, circumstances, personality, and vested interests, drifting helplessly with the current.

And the essence of all human self-control strategies is the attempt to use the smallest-scale free will, with the support of various rules, to overcome large-scale unfavorable factors from the bottom up and leverage larger-scale behavior. This is undoubtedly as difficult as climbing to heaven.

All the efforts, slogans, and even CTDP, are nothing more than attempts to create a pale and feeble ripple in this vast ocean. This is the tragedy that we who are weak in self-control naturally encounter.

17

Now, we can finally look back and understand more clearly what bottlenecks CTDP, as a typical local behavioral intervention strategy, has encountered.

The first bottleneck is the “Scale Limitation Problem”: CTDP can naturally only affect local behavior and cannot leverage the long-term factors behind these behaviors.

The core principle of CTDP is to amplify rational tendencies and reduce starting resistance in the short term (e.g., for an hour of focused work) through a series of ingenious mechanisms, thereby greatly improving the execution of a single behavior. At the microscopic scale, it has indeed shown amazing effectiveness.

But the problem is: our life is not a series of isolated hours pieced together. “Not willing to start the task right now” is just a superficial phenomenon. The larger-scale factors that cause this “unwillingness to start,” such as energy levels, emotional fluctuations, a clear sense of purpose, life rhythm, and even long-term habits, are the real essence.

When these large-scale factors are unfavorable to you, even if you use the most ingenious strategy to force yourself to study for an hour, the effect is often very limited:

- If you’ve been staying up late frequently and are physically and mentally exhausted, you won’t even rationally want to continue studying, and CTDP cannot solve the problem of staying up late itself.

- If you have no clear tasks or urgent deadlines recently, CTDP also cannot urge you to study on your own initiative, since you never had the habit of self-studying.

Therefore, the first fatal limitation of CTDP is that it can only affect microscopic nodes but cannot move the macroscopic factors that determine the keynote of our lives—it cannot make you energetic, nor can it make you mentally stable, let alone shake your habits or life patterns.

The second bottleneck is the “Steady-State Relapse Problem”: even if we temporarily change our state of life, the system will spontaneously fall back to its original stable mode.

When larger-scale factors like energy levels, life rhythm, mentality, habits, etc., are determined, the system will naturally form a series of highly stable behavioral patterns. For example, when you first get home at the beginning of a vacation, “playing games” and “scrolling through videos” might be the easiest life patterns to maintain, so your daily routine will likely cycle between “playing games” and “scrolling through videos.”

The problem with CTDP is that it can only temporarily interfere with certain nodes of the system. Even if you forcibly replace a few hours with a high-efficiency study mode, so what?

The system’s steady state is still the original steady state! If you stretch the time scale, these few hours of efficiency will still be drowned in a sea of gaming and video scrolling.

For the larger-scale (daily, weekly) steady states determined by habits, routines, and emotional states, these few hours of efficiency don’t even create a ripple, let alone bring about any change to the steady state itself.

This mechanism of spontaneous relapse is the fundamental reason why phenomena like “rebound,” “reverting to the original state,” and “intermittent efficiency” occur frequently.

The third bottleneck, and the most fundamental and desperate one, is the “Constraint Dissipation Problem”: any attempt to deviate from the steady state is consuming resources (like willpower) to maintain a metastable state, which is inevitably unsustainable.

When a person’s behavioral system forms a certain stable structure on a large scale, it becomes like a self-consistent ecosystem with a natural “steady-state attraction.” Any effort to break away from this steady state essentially means continuously investing various resources:

- Perhaps your precious willpower.

- Perhaps the ingeniously designed sunk costs of CTDP.

- Perhaps various rules, check-ins, and supervision.

But the problem is: these resources are finite. When you try to maintain a “metastable state” that deviates from the original steady state, even if you are very successful at the beginning, it will be worn down by continuous negative factors, and eventually, the constraint will collapse, and you will fall back to the original state. Even if you radically change the entire state at once, the resources and strength required are difficult to sustain.

Is it possible that there is a “next better steady state” that is higher than the current one?

It’s indeed possible. Sometimes, even when large-scale factors are unfavorable, you might accidentally be highly efficient for a few consecutive days. But unfortunately, such a state is often hard to come by, and before long, your life will return to its original state.

The most tragic thing is: almost all self-control methods lack the power to change the entire steady state in a long-term, holistic, and all-at-once manner.

These self-control methods are just using limited resources to support some local constraint rules, but they are powerless to achieve an overall migration. When the migration fails, these strategies fall into a “whac-a-mole” dilemma: you constrain studying here, and life order becomes chaotic over there; you establish a regular routine here, and your emotional state collapses over there.

This is because a large-scale negative steady state is often formed by the intersection of multiple small-scale negative steady states: staying up late leads to no energy, and when you are listless, you are more likely to get addicted to games; being addicted to games makes you chase stimulation, and chasing stimulation makes you stay up even later. This comprehensive negative state is like the snake of Changshan: strike its head, and the tail comes to the rescue; strike its tail, and the head comes to the rescue; strike its middle, and both head and tail come to the rescue.

Ultimately, you have to admit a cruel reality:

Given limited resources, all attempts to escape the current ground state face almost the same fate—a brief period of success followed by a rapid relapse, unable to achieve a true steady-state transition.

In summary, these three bottlenecks together form the insurmountable theoretical limit of CTDP. To fundamentally break through these limitations, we inevitably need a new, more holistic second-generation method.

And it was several years later that I finally found the key to truly solving these problems.

18

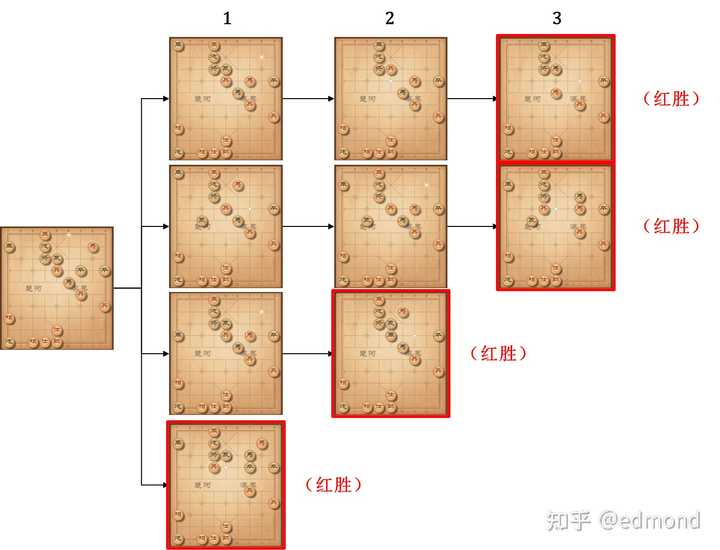

It was a rainy night. I had just received an offer for my PhD program but was stuck with visa issues. Out of boredom, I clicked on a chess commentary video. It was about the famous “Single Horse Checkmates King” game between Li Yiting and Chen Deyuan during the 1960 performance match when Sichuan chess players visited Wuhan.

Towards the end, the commentator mentioned:

At this point in the game, the red side has formed a “three-move kill” situation.

What does a “three-move kill” mean?

It means that once this situation is reached, the black side is already doomed. No matter how it responds, the red side can always checkmate the black king within three rounds. All of black’s struggles can only delay the time of its checkmate, and if it struggles improperly, it might even bring that time forward.

So, why did the black side end up in such a predicament?

Of course, it was because its previous move was wrong. If the black side could take back its move and return to the previous step, it might be able to avoid falling into the “three-move kill” dead end. If, after backtracking to the previous step, it was still a “four-move kill” and still couldn’t avoid being checkmated, then the move before that was already wrong. And so on.

You will find that if you keep backtracking, you will inevitably be able to trace back to a certain move where the hope of black winning reappears! (At least within the search range of a computer, red cannot find a guaranteed win).

And this very point is the key to breaking through with the second-generation method.

Let’s go back to the example of playing on the phone while lying on the sofa.

When we are lying on the sofa scrolling through videos, we have indeed inevitably entered a vicious cycle. But what if we trace back?

- To avoid starting to scroll through videos (99%:1%), we have to avoid holding the phone on the sofa (80%:20%).

- To avoid holding the phone on the sofa, we have to avoid bringing the phone to the sofa (60%:40%).

- We can continue: to avoid bringing the phone to the sofa, we have to avoid getting into a state where it’s easy to bring the phone to the sofa (50%:50%)…

—Often in this process of tracing back the series of events, the further you trace back to an earlier node, the smaller the preference gap between the two options becomes!

Thus, we have finally discovered an exciting pattern:

For any seemingly inescapable “inescapable zone,” we can inevitably trace back to a certain node—at this node, the preference gap between the two options is small enough to fall within the effective intervention range of free will, giving us the ability to truly avoid entering the final negative dead end.

In other words, every seemingly powerful, large-scale negative steady state can be mapped to a weak, small-scale effective intervention node!

And this node is the true boundary of the “inescapable zone.”

19

Here’s where things get interesting:

As mentioned earlier, the types of negative states we face in life are actually extremely limited and highly repetitive. And for any given negative state, we can always map it back to an effective intervention node by backtracking.

Therefore, if we apply a precise constraint to it, we can achieve a “four-taels-moves-a-thousand-catties” (leverage) effect, preventing trouble before it happens and avoiding entering those negative states from the very beginning. This constraint is the local optimal solution for this situation.

What’s even more delightful is that since the negative states themselves are repeatable, the “local optimal solutions” for these states are naturally also repeatable!

Let’s take a few examples:

- “Not bringing the phone into the bedroom from the start” is many times easier than “bringing the phone into the bedroom and then resisting the urge to scroll through it.” Therefore, not bringing the phone into the bedroom from the start is naturally the optimal solution to the “scrolling on the phone before bed” problem.

- “Showering immediately after getting home when there’s nothing to do” is many times easier than “forcing yourself to get up and shower when you’re already lying on the sofa playing with your phone.” Therefore, making a rule to start showering within 15 minutes of getting home is the optimal solution to the “showering procrastination” problem.

(Where the binding force for this rule comes from will be explained later.)

In board games like Chess and Go, such a repeatable optimal sequence of operations for a specific situation is called a “Joseki.”

The so-called Joseki is actually the local optimal solution summarized by countless predecessors after in-depth research: in a specific local situation, both black and white players must strictly follow the Joseki. If either side deviates from the established pattern, they will inevitably leave an opening.

Even in the ever-changing game, by mastering local Joseki one by one, players can greatly improve their overall skill level.

And we can do just the same, like a Go player learning Joseki, using a “divide and conquer” logic to crack the negative states in our lives one by one:

- First, we can identify the typical negative problems in our lives.

- Each negative problem can be further broken down into several negative steady states.

- And each negative steady state can be mapped back to a corresponding effective intervention node through backtracking.

- Finally, for each intervention node, we can tailor a precise “Joseki” to crack it.

In this way, we can concentrate our limited self-control resources precisely on those truly critical nodes, and deal with those highly repetitive negative states with a dimensionality reduction attack, one by one.

If four taels can move a thousand catties, why not use eight taels to move two thousand catties, twelve taels to move three thousand catties, and sixteen taels to move four thousand catties?

20

Even better, eight taels might move more than just two thousand catties.

Suppose we have truly found a local Joseki and are willing to invest certain resources (e.g., method design, willpower, or external constraints) to implement it, successfully “banning” a certain negative state from our lives—for example, never again lying on the sofa with a phone, or always taking a shower immediately after getting home.

Then, because its scope of action is long enough, this “Joseki” itself will also join the many large-scale factors that affect our life’s steady state, becoming one of them!

Is the steady state at this point still the same old steady state?

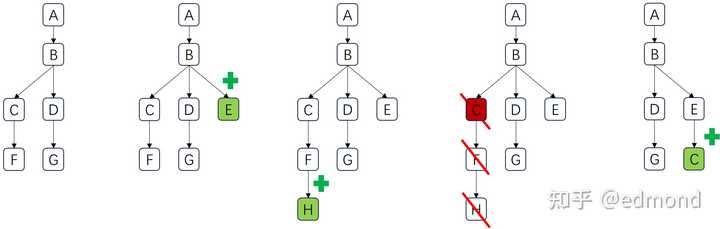

Obviously not. If we denote the initial steady state as , then after the first Joseki is successfully introduced, your life will gradually enter a slightly improved metastable state . In the new steady state , because the overall state has improved a little, the difficulty of introducing a second Joseki will be somewhat reduced. Similarly, after the second Joseki is added, you enter a more optimized metastable state , and in , introducing a third Joseki will become even easier.

For example, if you henceforth “stop playing on your phone on the sofa,” it will be slightly easier to implement “showering immediately after getting home.” If you get into a refreshed state by showering immediately after getting home every day, implementing “not scrolling on your phone before bed” will also become a tiny bit easier because you’ve solved the shower procrastination problem.

Each new Joseki introduced may produce a “1+1>2” effect, ultimately improving your life in a “salami-slicing” manner, gradually transitioning towards a better long-term steady state, step by step.

As Sun Tzu’s Art of War says: “The skilled warrior wins victories where victory is easily gained.”

By solving the simple problems, the originally medium-difficulty problems become simple problems. If we then conquer this new simple problem, the originally difficult problems also become simple problems.

From beginning to end, we are only solving simple problems.

Alright, we’ve found a series of Joseki, each capable of preventing entry into a negative “inescapable zone” from the outset. But to truly achieve a large-scale steady-state transition, we still have to face that most fundamental challenge—the problem of limited binding force.

As analyzed earlier, all self-control strategies are essentially using limited resources to support some local constraint rules. This inevitably leads to a “whac-a-mole” dilemma: you were talking so nicely about moving from to , and to , but what might actually happen is that you simply don’t have enough energy to maintain all these Joseki.

- When you try to add a new Joseki, one of your old ones might suddenly collapse.

- Or you might push too hard, trying to implement a overly demanding Joseki from the start, and before it can improve your overall state, maintaining it exhausts all your resources.

- Or you might introduce a new Joseki that is incompatible with your existing ones, causing the entire system to crash instantly.

In other words, the order in which you introduce the Joseki is also crucial. Not just any random order can support you in reaching the next steady state. Furthermore, where does the binding force for so many Joseki come from?

To completely solve this difficult problem, we need to introduce a new, ingenious algorithm—the “Recursive Backtracking Algorithm.”

21

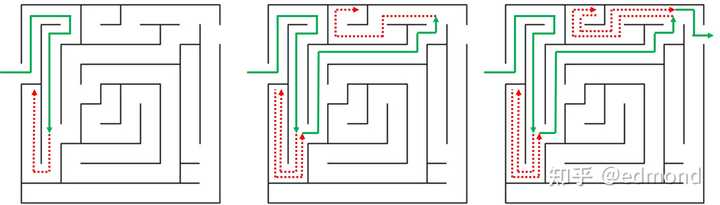

The so-called Recursive Backtracking Algorithm is actually a classic algorithmic idea widely used in computer science. It is usually used to solve problems where you are faced with a system of extremely vast possibilities (such as navigating a maze or playing chess), and you need to find a feasible, or even optimal, path with limited resources.

The most typical example is the maze problem: